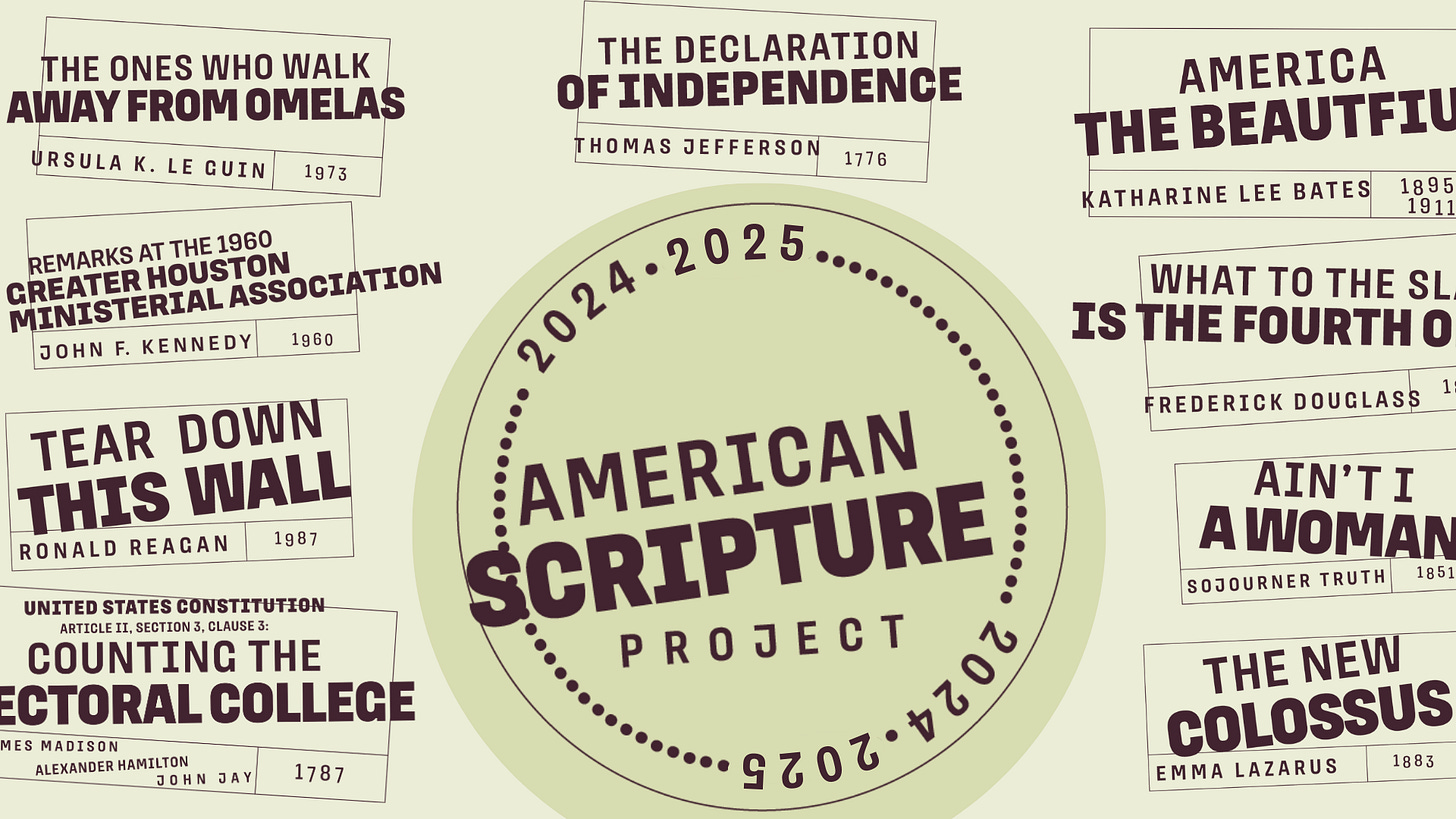

Series 1 Texts

Nine Documents to Get You Started

Texts to Be Considered

Calling a document “Scripture” separates it from its mundane purpose and elevates it to a source of moral guidance (even if we gain wisdom from it through disagreement). The potential library of American scripture is vast. The texts for this program were selected using the following four criteria: (1) they incorporate the fundamental American narrative ideas of liberty, equality, exceptionalism, and justice; (2) they attempt to represent both normative and marginal voices from our national history; (3) they demonstrate the varied ways (what we call “mechanics”) that narrative can be used to inspire citizens; and (4) they are old enough that groups can avoid being drawn into arguments about current events.

Session 1: “The New Colossus,” Emma Lazarus: Written by a Jewish woman, the poem distinguishes the American experiment from other famous civilizations in human history and resonates with personal histories of migration. Simultaneously, it demonstrates how mere words on a page can transform the country, going so far as to subvert the purpose of a massive civic project.

Session 2: “The Declaration of Independence,” Thomas Jefferson: As one of the most inspiring and effective documents in human history, the Declaration is unparalleled in its power. Yet its use of the word “savages” to describe Native Americans, and Jefferson’s personal history, raise contradictions at the core of its argument for absolute human equality. Groups will have to confront the spiritual challenge of our disappointment with incomplete aspirations.

Session 3: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass: Using familiar biblical texts, Douglass shines a spotlight on perhaps our most important national ritual, the celebration of Independence Day. In so doing, he simultaneously attacks the way Americans undermine our national narrative of liberty while upholding the true meaning of that narrative.

Session 4: “Tear Down this Wall,” Ronald Reagan: At the height of the Cold War, when the country faced terrifying nuclear peril, Reagan used the power of sacred space to argue for American exceptionalism and freedom. Because this speech was delivered within the living memory of many participants, it will challenge their ability to separate national narratives from personal partisan beliefs.

Session 5: “Ain’t I A Woman,” Sojourner Truth: Delivered by an illiterate, formerly enslaved woman, but published in two different versions separated by 12 years, this cornerstone of feminist activism demonstrates the ways that texts can be used and misused by audiences. Because this session involves careful textual comparison, it relies on familiar concepts of scripture study and allows groups to confront their internal biases.

Session 6: “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula K. LeGuin: Relying on the great American narrative of a New Jerusalem, LeGuin questions our individual obligations when we realize we are implicated in social injustice. And as a short story, “Omelas” draws readers into a painful confrontation with the reality of American inequality and exploitation.

Session 7: “Remarks at the 1960 Greater Houston Ministerial Association,” John F. Kennedy: Given the anti-Catholic attacks on Al Smith during the 1928 Presidential campaign, Kennedy presents a vision of an absolute separation of Church and State. Studying this issue in a religious context asks groups to consider how faith traditions and behavior can positively and negatively influence our political system.

Session 8: “America, The Beautiful,” Katherine Lee Bates: By setting her aspirations for the country’s moral beauty against its physical grandeur, Bates subtly pushes the country to address its founding contradictions. Because most participants will know only the first and last stanzas, facilitators can explore the sophisticated moral agenda in the second and third stanzas (where, incidentally, Ray Charles began singing in a famous performance during the Vietnam War).

Session 9: The United States Constitution, Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 3 (the Counting of the Electoral College Vote): This dense and obscure passage of the Constitution appears mundane, yet it describes an elaborate ritual to accompany the selection of a new president. Given that this was the precise Congressional event attacked on January 6, 2021, the text elevates the importance of rituals in communicating meaning and maintaining national cohesion.